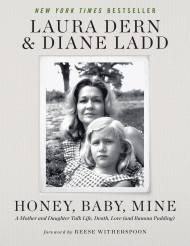

What Really Happens in Vegas

True Stories of the People Who Make Vegas, Vegas

Contributors

By James Patterson

By Mark Seal

Read by Phil Morris

Formats and Prices

Price

$24.99Format

Format:

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

- ebook $16.99 $21.99 CAD

- Hardcover $30.00 $39.00 CAD

- Trade Paperback $10.99 $13.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback (Large Print) $34.50 $43.50 CAD

Also available from:

What happens in Vegas stays in Vegas—until now. James Patterson shows the real Vegas in a dazzling journey through “lively tales of those who labor and dream in Sin City” (Kirkus).

“Wild and wonderful…The magic of Sin City doesn’t just happen. Patterson and Seal tell its secrets in beautifully presented snippets that often overlap not just surprisingly, but charmingly too.” —Telegraph (UK)

- Las Vegas is on Luxury Standard Time: every clock in the airport is a Rolex.

- No dream is too big, no wish is too small—the VIP hosts in Vegas fulfill guests’ every (legal) desire.

- Jackpots hit when least expected. The Nevada Gaming Control Board has days to find a man who unknowingly won over $200,000 at the slots.

- “I love love”: the inventor of the Elvis impersonator wedding and the drive-thru wedding has performed hundreds of marriages—and believes in them all.

- Glamorous yogis take a helicopter across the desert to the Valley of Fire, where they perform sun salutations to the glory of Las Vegas.

- A gambling VIP “whale” loses $1 million at the casinos, yet still leaves saying, “Had a great time. I’ll be back.”

In What Really Happens in Vegas, full of surprises for both newcomers and Las Vegas regulars, James Patterson and Vanity Fair contributing editor Mark Seal transport readers from the thrill of adrenaline-fueled vice to the glitter of A-list celebrity and entertainment.

-

“Lively tales of those who labor and dream in Sin City…the entertainment value is high.”Kirkus

-

“Uptempo, vivid, and fun … an entertaining ride.”Publishers Weekly

-

"Unusual facts and tales about Las Vegas... the inner workings of those who live and work in Las Vegas and those who make the city come alive... reads like a novel."Library Journal

-

“Wild and wonderful…The magic of Sin City, it turns out, doesn’t just happen. It’s carefully created within the walls of all manner of buildings, from advertisement firms to topless bars, by dedicated professionals – people whose lives are at once more mundane and more strange than anyone, until they read this book, could guess.”Telegraph (UK)

-

“A breezy, nonstop narrative capturing the essence of a crazy, wide-open town … a dazzling and fun account of America’s entertainment capital.”New York Journal of Books

-

“Especially entertaining…What Really Happens in Vegas is a must-read for anyone wondering what really happens in the city Hunter S. Thompson once dubbed ‘the savage heart of the American Dream.’”Air Mail

- On Sale

- Dec 4, 2023

- Publisher

- Hachette Audio

- ISBN-13

- 9781668623411

By clicking 'Sign Up,' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use

TRAILER

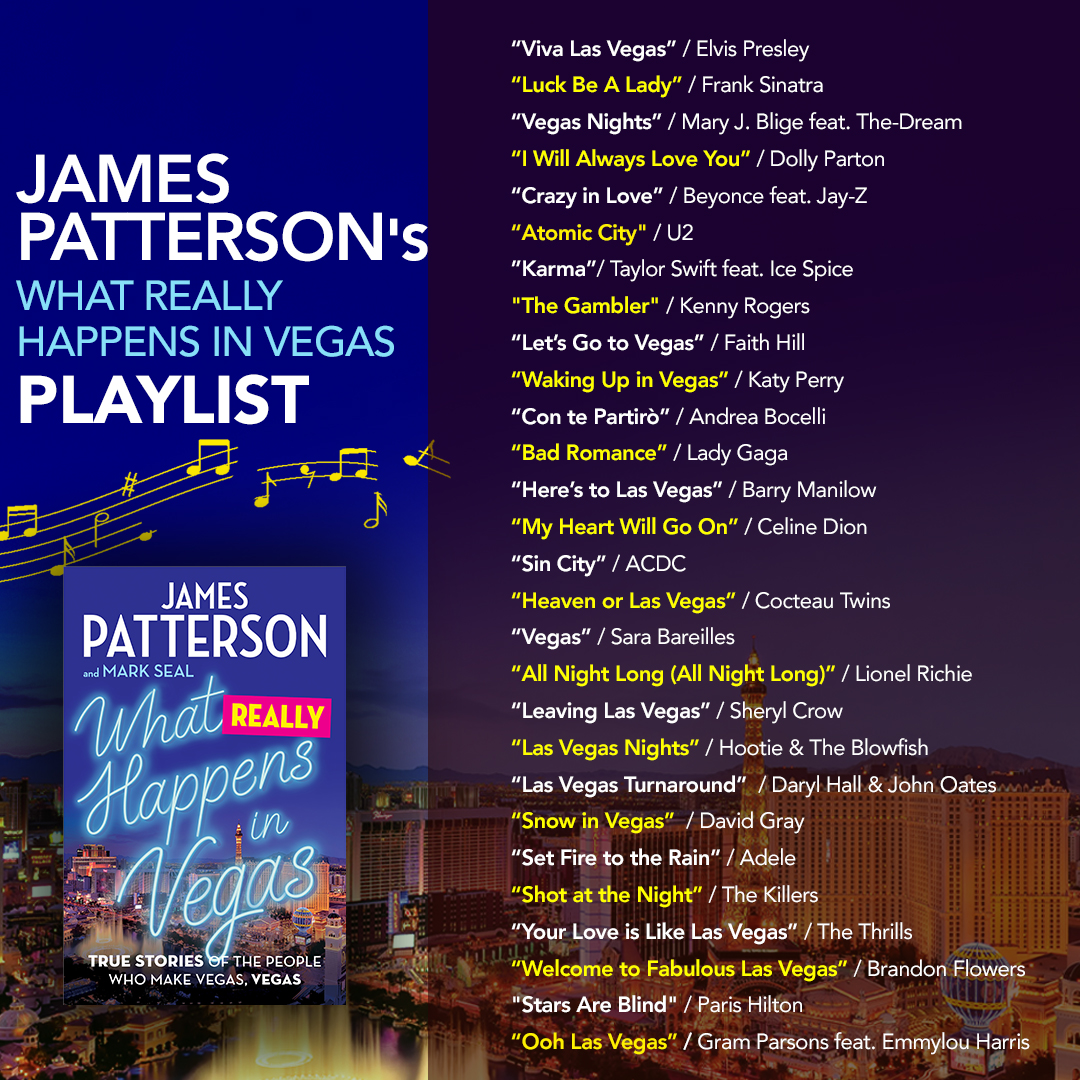

JAMES PATTERSON’S WHAT REALLY HAPPENS IN VEGAS PLAYLIST

What's Inside

Read chapters 1–4

♣ ♣ ♣

Chapter 1

WELCOME TO LAS VEGAS

HARRY REID INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT

THE CITY BEGINS casting its spell at the airport.

Harry Reid International isn’t just a portal to the city, the place where one million visitors arrive and depart every week from around the world. It’s the opening act, the master of ceremonies, designed to seduce new arrivals with a shimmering display of slot machines, shopping, dining, advertising, and glitz. Set on one of the largest footprints in southern Nevada, covering 4.4 square miles, the airport’s glass-sheathed towers shimmer by day in the desert sun and glow in the neon-lit night.

In an office tucked behind a Starbucks and a TSA security checkpoint sits the airport’s director, Rosemary Vassiliadis. Under her watchful eye, the airport runs twenty-two hours a day, pausing only for two hours just before daybreak. “We never lock our doors,” says Vassiliadis. There are nearly one thousand flights every day, with more than one hundred direct routes from big cities like New York and Los Angeles and London as well as towns like Bozeman, Fort Collins, and Humboldt. On many Sundays and Mondays, Harry Reid has served more people than any other airport in America.

So many visitors pass through the terminals every day, as many as 52 million in one year, that the airport has its own police and fire departments. The single biggest carrier, Southwest Airlines, has commandeered an entire concourse—Concourse C, in the ever-expanding Terminal 1—shuffling 1.5 million arriving and departing passengers in November 2022 alone, according to one published report. Many of the larger casinos, from Caesars Palace to the MGM Grand, operate their own charters for elite customers at the adjacent private air terminals at the airport, and private helicopters can be seen taking off for aerial tours of the Grand Canyon.

Travelers arriving at one of the one hundred ten gates are met with a blast of air conditioning that belies the summer heat, which regularly rises above one hundred degrees. These dreamers and schemers arrive wearing slick suits and skimpy dresses, formal tuxedos and wedding gowns, cargo shorts and flip-flops—“things they don’t wear at home,” says Vassiliadis. They come for love and lust, superstar concerts and trade conventions, magic shows and boxing matches, and, threading through it all, action. They have practiced their bets during their flights, reading how-to books that promise secrets for beating the house. What many don’t realize is that the house begins here, at Harry Reid International Airport.

“Give them Vegas as soon as that jet-bridge door opens,” Vassiliadis likes to say, “and keep Vegas going until it shuts.”

It’s a creed reflected in the airport’s every detail. From the moment passengers disembark, rowdy and ready for fun, Vegas begins its seduction. At the airport, the hours are set to Luxury Standard Time: every clock, in every terminal, is a Rolex. Even the floor, which Vassiliadis had first seen in the Disney Store at Caesars Palace, is designed to induce awe: a swirling terrazzo, glittering with bright shards of broken mirrors. Here, the fancy floors announce, money is no object, glories abound, and wonders never cease.

“A lot of bling,” Vassiliadis says of her airport. “A lot of bling, and branding everywhere.”

Arrivals are eager for the action, giddy with anticipation. “They get off the plane and they’re ready to go,” says one airport official. “They want to get into their cab. Get to the hotel, get to the casino, get to the action. They want to get on their way. They’re yelling, ‘Vegas, baby!’ and things like that. They’re getting the party started before they even leave the airport.”

Slot machines are ubiquitous. There are more than one thousand one-armed bandits throughout the airport, strategically arranged in mazes outside each gate and in enticing lines next to the baggage claim carousels. The machines were first installed in 1968, and the numbers grew throughout the 1970s. Originally they were coin-operated slots, but today the entire collection is digital, with constantly upgraded contraptions that offer ever-mounting jackpots. In almost every terminal, the blaring Wheel of Fortune slot is a main attraction.

“Our surveys let us know that our visitors want to hear the slot machines,” says Vassiliadis, who ensures that the volume on the slots is turned up loud. “It’s not noise to them—it’s music, it’s attraction. That’s why they come here. Only two airports in the nation have slots—us and Reno.”

The jangling din of the slot machines tends to obscure the actual music, the soundtrack pouring from unseen speakers throughout the airport—the legendary music of Las Vegas, a nonstop playlist featuring the artists and songs most associated with the city. Elvis’s “Viva Las Vegas,” Barry Manilow’s “Here’s to Las Vegas,” and Frank Sinatra’s “Luck Be a Lady” along with tunes by Céline Dion, Sammy Davis Jr., Gwen Stefani, and the Killers.

“We have customized our overhead terminal music to the entertainers who made their careers in Las Vegas—the Rat Pack, Elvis—along with modern-day entertainers with residencies here, and, of course, songs about Las Vegas,” says Vassiliadis.

Vegas is surely one of the most marketing-driven cities in the world. Thanks to the Las Vegas Convention and Visitor Authority’s massive marketing and surveying operations, even before passengers land at the airport, Vegas knows the purpose for their visit, the number of nights they’ll stay, their “gaming behavior and budget,” what they plan to do and see, and more. Everything at the airport is scaled to reflect a grandiose vision of bigger, better, more—the mammoth terminals with their skyscraping ceilings, their soaring escalators, and their endless vistas of slots and shops and restaurants.

Past the vast concourses of temptation lies a centerpiece of the airport. Known as the Poker Chip, the custom-made floor mosaic in the baggage claim area celebrates the skylines of old and new Las Vegas. On one side of the Poker Chip is the past: long-gone resorts like the Dunes, the Landmark, and the Desert Inn, where billionaire hermit Howard Hughes once holed up. On the other side is the present: the towering Stratosphere spire, the Bellagio, the Wynn, the volcano at the Mirage.

Once the passengers descend into the baggage claim area, they find the Liquor Library, a megastore selling every conceivable spirit that claims to be the only non-duty-free liquor store in an airport baggage claim area in America. “Vegas starts at the Liquor Library,” a sign boasts, inviting visitors to stock up on booze while they’re waiting for their luggage. “We know why you come to Las Vegas and the Liquor Library is here to help.”

From there, the skyline of the Strip beckons, shimmering in the distance like a mirage. It’s so close, only three short miles from the airport, that some people believe they can run to it—and some, fortified by spirits from the flight or provisions from the Liquor Library, are probably tempted to try.

♣ ♣ ♣

Chapter 2

THE RIDE

WAYNE NEWTON BOULEVARD

OUTSIDE THE AIRPORT terminal, on Wayne Newton Boulevard, passengers catch a lift to the Strip. It’s fitting that the street ushering visitors into Vegas is named for Mr. Las Vegas himself, the city’s resident entertainer for more than six decades. A high school dropout originally from Virginia, Newton, like most who come to Vegas, arrived from somewhere else. It was 1959, when he first performed in what was to be a two-week “tryout” at the old Fremont Hotel and Casino. It instead lasted forty-six weeks, and Wayne Newton never really left. Today, on the boulevard that bears his name, taxis and limos and car services line up to whisk the new arrivals to the visions of glory that have drawn them to Las Vegas, just as they drew the teen-aged Wayne Newton.

Chauffeur Raymond Torres is waiting for his first ride of the day. Suit, tie, starched white shirt, leather shoes, black leather gloves, and his signature sunglasses—everything spotless. “I’m like a fireman,” he says. “Once the phone rings, I get suited and booted, and I’m ready to go.”

Out in the airport parking garage, his jet-black Rolls-Royce Ghost awaits. Torres stands outside baggage claim with an iPad bearing the name of his client. If it were one of the celebrities he has chauffeured in the past—Mariah Carey, Warren Buffett, Christina Aguilera, Brad Pitt, or Ryan Seacrest—he would be waiting across the tarmac at one of the airport’s private jet terminals. “A lot of times you don’t even know who you’re picking up until they’re in the car,” Torres says. “Most of the celebrities have code names. Like Nicolas Cage. He lived here when I drove him and I’d take him out on the town. But his security would only give me the code name on the paperwork, because they don’t want you calling someone and saying ‘Hey, I’m picking up so-and-so.’

“Everybody becomes their true selves in Las Vegas,” Torres says. He sees it happening every day in his rearview mirror: the trophy wife who becomes a high-rolling gambler, the straitlaced executive who becomes a reckless ladies’ man, the schoolteacher who takes a temporary job as an exotic dancer. This morning, Torres is waiting for Toby, one of his top clients. Back home, Toby’s built a career in financial consulting. But in Vegas, he reinvents himself as a renegade gambler, a high roller going by the nickname Thunderboom. He comes to the city for months at a stretch, living in the high-end resorts on the Strip while he tries his luck at the casinos.

Torres is affiliated with a group of seven chauffeurs known as the Untouchables, who have access to a sizable fleet of luxury vehicles. But for clients like Toby, only Torres himself will do—because, says Toby, “he’s so trustworthy.”

Torres, in a sense, is emblematic of Vegas, a city with a criminal past and a corporate present. Today, he’s a chauffeur for the stars. Once, he was accused of stealing from one of them.

If passengers are interested, Torres tells them his story of growing up in Las Vegas, where kids grow up fast. His father, who owned a roofing company, took him to his first strip club, Crazy Horse, when he was around sixteen. To help him gain entry, his dad took some tar and painted a moustache on his face. Before long, young Ray was embroiled in a life of crime, as a thief and a drug dealer. Vegas being Vegas, there was always plenty to steal, and plenty to deal.

In 1995, when he was only twenty-six, Torres played a central role in a high-profile art scam. He ended up with between two and three million dollars’ worth of paintings by the likes of Dalí, Matisse, and Renoir in his possession. But the stolen artworks, which he’d planned to fence on the black market, didn’t belong to just anybody. They belonged to Mr. Las Vegas himself, Wayne Newton.

Torres tried to sell the paintings to Colombian drug dealers in exchange for one hundred ten pounds of cocaine. But the drug dealers were working as informants for the FBI and the Drug Enforcement Administration. A sting operation closed in, and Torres was convicted and sentenced to nineteen years and seven months in federal prison. When he was released after eighteen years—his sentence shortened for good behavior—he converted his criminal past into a shiny new future. One of his former associates had landed a job in a casino and arranged a job interview for Torres at a limousine service. The manager of the company asked Torres about his years in prison, then posed a pivotal question.

“How’s your driving record?” he asked.

“I haven’t had a ticket in eighteen years,” Torres replied. The manager laughed, and Torres was hired.

♣

Ray Torres is summoned to the airport this morning via a text on his cell phone. He calls the phone his office because he doesn’t have an office, and his phone is forever pinging with calls and texts and emails. Being a chauffeur in Vegas means doing more than just driving. “If somebody wants a helicopter,” Torres says, “if somebody wants a jet, if somebody wants tickets at the fifty-yard line or bottle service at a club, if somebody wants restaurant reservations or designer clothes or some company for the evening, whatever somebody wants—just about anything—I can provide for them. Except anything illegal.”

The text he got from Toby last night was simple: Vegas, baby, 8 a.m. pickup. Ready to rock and roll.

Now his client—bearded, middle-aged, his business suit traded for a red hoodie and baseball cap—is sitting in the back of the Rolls, headed to Resorts World, which he’ll call home for the next month, maybe longer. When Toby’s in town, Torres is on call, driving him everywhere: to the grocery store, to a restaurant or the casinos, on all-night club crawls. “Ray responds immediately,” Toby says. “I trust him with my life. If it’s midnight and I call him and say, ‘I’m bored, me and my friends wanna go to a strip club,’ he’s on his way.”

As they roll out of the airport, Toby is ready to indulge in everything Vegas has to offer. But first comes the ride, a preview of the coming attractions, starting with the line of gigantic billboards advertising shows, spectacles, resorts, or restaurants, each bigger and grander than the last. The front side of the billboards—the ones facing visitors heading into the city—feature seductive come-ons for Lady Gaga at the Park MGM or the magician Shin Lim at the Mandalay Bay or Thunder from Down Under, the all-male strip revue at the Excalibur. The back side of the billboards—the ones seen by those leaving Las Vegas—feature ads for personal injury lawyers or for lease signs, or nothing at all.

Nobody’s selling to anyone leaving Las Vegas.

Turning off the street named for the entertainer whose stolen paintings sent him to federal prison, Torres merges right onto Paradise Road and takes a left onto Tropicana West, taking the longer, more scenic route into town. In the distance, he can see the Mandalay Bay Resort and Casino on the Strip’s southern edge, next to the massive glass pyramid of the Luxor. Straight ahead and to the left are the pointed castle towers of the Excalibur, and the Tropicana, built in the late 1950s and updated as a gleaming ivory tower. On the right is the sprawling, emerald-green MGM Grand, with its fifty-ton bronze lion, its 171,500 square feet of gaming space, and its hidden high-roller resort and private casino, the Mansion, reserved for the biggest players. “I’ve driven clients there who are sitting in the front seat next to me with bags full of money,” says Torres. “Billionaires. I’m talking, like, Louis Vuitton bags full of money. Staying at the Mansion MGM Grand for, like, a week.”

“Those villas are nice,” says Toby, who sometimes stays at the Mansion himself. “Speedy Lee used to stay there and play baccarat in their high-roller room.” Speedy Lee is the nickname of a legendary gambler. “Speedy Lee has eight girls with him in long red dresses, like his harem. He plays on two tables at the same time, hooked up to an oxygen tank so he can play for seventy-two hours straight, three hundred fifty thousand dollars a hand on each table, the girls just sitting behind him, watching. And everything has to be feng shui in the room. They spray this special spray in the air to clear the energy, because he’s very superstitious. When I saw him, I was like, How small am I playing in my life? Speedy Lee is going all out!”

“When Speedy Lee was at the Mansion, he had limos waiting twenty-four-seven,” Torres recalls. “I was one of the drivers waiting to pick him up, to take him whenever he needed to go. But sometimes he’d have drivers waiting and he never came out. Sometimes you wouldn’t see him for hours or days, but there would always be a line of limos waiting for him, both a day shift and a night shift. And every time he got in the car, he always tipped at least a few hundred bucks.”

Torres takes a right onto Las Vegas Boulevard, and passes New York–New York, with its replicas of the Chrysler and Empire State buildings. The ultrahip Cosmopolitan (“Just the Right Amount of Wrong”). Planet Hollywood. The Eiffel Tower and Arc de Triomphe of the Paris Hotel and Casino, which commands the skyline across from the Bellagio. Each has its particular come-on: to gamble, eat, drink, dance, and revel in almost anything that money can buy. Each one prompts a memory.

Torres remembers a husband and wife he used to ferry from the airport. “Wholesome family, kids and everything,” he says. “The husband would come every once in a while by himself, and I’d take him to a strip club. Then next trip, he’d come with his family. One time, I picked him up from the private airport and he looked like crap. Obviously drunk, in shorts and flip-flops. I’m like, ‘You all right?’ And he says, ‘Nah. I’m getting a divorce.’ ”

Toby leans forward. He’s gone through a divorce of his own. “And afterwards I went on a Vegas rampage to make up for the lost time.”

“The guy goes, ‘It was my fault,’ ” Torres continues. “He said that him and his wife used to come to Vegas and stay at a hotel together. They came to an agreement where he would go play around, she would go play around, and they’d come back and share their experiences.” For the wife, though, one of those experiences turned out to be more than just a playdate. She met somebody she really liked, and she left her husband.

“She ended up staying with the other guy,” says Torres. “Very dumb,” says Toby. He recounts his own story of coming to Vegas after his divorce. It was a few years ago, he says, when the Patriots were playing Atlanta in the Super Bowl. He had a reservation to watch the game with a friend at Sapphire, which bills itself as “the World’s Largest Gentlemen’s Club.” Before long, the manager came over to their table.

“You guys need anything?” the manager asked. “Yeah,” Toby told him. Soon a dancer was at his table, helping him forget about his ex-wife. “After my divorce,” he explains, “I was like, I’m just gonna enjoy my life.”

Which is exactly what he’s come to Vegas to do.

They pass the Bellagio, the Italianesque monolith rising behind its enormous lake with its famous Fountains of Bellagio. The sight triggers a new story from Torres, this one about Andrea Bocelli, the blind Italian operatic tenor superstar.

“Andrea Bocelli is one of the nicest guys,” says Torres. “When I drive him, I’m always invited stage side to enjoy his concert.”

Bocelli is fascinated by Las Vegas, even though he can’t see it. He sits in the front seat, next to Torres, attuned to everything around him.

“Ray, what kind of car is this?” he’ll ask, according to Torres.

“It’s a Cadillac Escalade,” Torres will say. “What year?” asks Bocelli.

When Torres tells him, Bocelli reaches out and turns on the radio, knowing exactly where to press the touch screen.

“It’s amazing,” says Torres. “Then he’ll roll down the window and he’ll just listen to the city as we’re going down Las Vegas Boulevard. He doesn’t speak much in the car, but sometimes he’ll sing. Last time, a Christian song came on and he started singing along with it. But most of the time he’ll just roll down the window and listen.”

And feel the red-hot energy of the town, palpable even to someone who can’t actually see it.

Passing the white expanse of Caesars Palace brings to mind another musician. “I drove for Elton John when he was in a residency at Caesars,” Torres says, referring to the common practice in Vegas of having a performer appear in a resort showroom for an extended period, often months or years at a time. “Another driver and I would pull right into the garage connected to his dressing room, where his butler and chef would be waiting to serve us food and drinks while we watched the concert from a big-screen monitor in the dressing-room lounge.” Next is the Mirage, where Torres says he once picked up Brad Pitt. “My job was to take him to Signature Flight Support, which is a private airport,” he recalls. “He had a meeting in LA just to sign some papers, and he was gonna fly straight back.

It’s only a forty-five-minute flight, but I wound up waiting at the airport for a few hours for him to return from LA. When I dropped him off back at the hotel, the security guard tipped me out. I didn’t even look how much it was. But I waited because I saw Brad saying something to the bodyguard. Before I pulled off, the guard tapped at the window and said, ‘Wait, give me back that thirty dollars.’ Then he handed me a hundred. Brad must have asked him how much he gave me, and told him to give me a hundred bucks.”

Farther along are the shimmering golden towers of the Wynn, home to one of the city’s most exclusive nightspots: a supper club called Delilah. “Clients will call and say, ‘Ray, we wanna go skydiving, off-roading, hiking, we wanna go see a show, have dinner at a certain place,’ ” says Torres. “Delilah is the hot new restaurant. Last time I checked, they were booked for the entire year. You couldn’t even get in unless you knew somebody.”

“Yeah, you got me into Delilah,” Toby interjects. “That’s the newest, hottest place in town.”

“A lot of celebrities go there, a lot of socialites,” says Torres. “I was there once with a major comedian and he was so taken with Delilah that he pulled out his cell phone to take a photo. I’m like, Man, what are you doing?”

Torres got an autograph for his daughter from Ryan Seacrest once, when American Idol was being filmed at the Wynn. Toby’s stayed there, too. “Right on the golf course,” he says. “Steve Wynn used to have the last villa, a three-story villa. If you were playing golf, you could see his artwork through the glass walls. He had that one that was just painted red and that was like fifty million dollars, and you could see it from the golf course.”

Las Vegas Boulevard continues north, and soon, they arrive at Resorts World, the first new major resort to be built in Vegas since the Cosmopolitan in 2010, and the most expensive at $4.3 billion. Its 59-story tower is home to three hotels and a casino that encompasses 117,000 square feet—which architect Paul Steelman designed to create an illusion of not merely inhabiting another world, but becoming another person:

“The key to a successful casino design is to imbue visitors with a feeling of being the suave and sophisticated James Bond,” says Steelman. “The casino’s interior is carefully orchestrated to create a profound sense of empowerment, drawing patrons into a realm where they feel extraordinary. Noticeably lower ceilings help foster a more intimate and exclusive atmosphere, while warm and flattering lighting enhances the allure of the space, making everyone appear and feel their best. Curiously, you won’t find any mirrors adorning the walls, for looking into one would only shatter the illusion of being a debonair secret agent.”

This is where Toby will be spending the next month—or longer, if the cards are kind. He’ll be up for the next twenty-four hours but won’t start gambling until after midnight.

“I play better after midnight,” he says as he steps out of the Rolls. “My brain relaxes then, and I go into a theta brainwave state, like a Buddhist monk who has been meditating for thirty years. Only I’m at the baccarat table in Vegas.”

Torres is already standing by, handing Toby his luggage, offering him a ride anywhere he wants to go.

“When you pick me up later,” Toby says, “I’ll have more stories for you.”

His very own Las Vegas residency is about to begin.

♣ ♣ ♣

Chapter 3

THE ARRIVAL

THE WYNN

FOUR MIDDLE-AGED MEN from Atlanta are in a taxi headed to the Wynn, a forty-five-story, copper-colored curved building resembling a cupped, welcoming hand. This is the last—and most spectacular—resort built by the Las Vegas impresario Steve Wynn, who reinvented the city with his colossal resorts. The men from Atlanta have stayed in most of them. The Golden Nugget, the first luxury resort downtown. The Mirage, with its South Sea islands theme. Treasure Island, with its full-scale pirate battle raging out front. The Bellagio, an Italian lake resort on steroids. And now, Wynn’s pièce de résistance. The one he named after himself. The one that tops them all.

Back home, Damon Raque—who serves as both cheerleader and guide for the men from Atlanta—is the owner of a wine storage and tasting lounge called Bottle Bank. But in Las Vegas, he becomes the ultimate thrill seeker: every trip is an attempt to top the one before with new extravagant activities that will, as he says, “make my buddies say ‘Wow,’ or ‘What an experience,’ or ‘Man, that was amazing!’”

Raque’s first stays in Vegas as a bachelor in the 1990s were at the Palms, whose young owners “really brought the nightlife wave to Las Vegas” with their Playboy Club and Playboy Suite, complete with a replica of Hugh Hefner’s circular bed. Then Raque moved on to the raging pool parties at the Hard Rock, where noon was the new midnight and the champagne flowed like water. He has sampled every hot new nightspot in town, swum with the dolphins at the Mirage, raced Baja trucks in the desert, done the skydiving and the rock climbing, taken master classes in fine wine at the Rio and prepared truffle risotto in a cooking class with Frank Sinatra’s granddaughter at the Wynn. Whatever money can buy in Las Vegas, Raque has done it. Been there, spent that. But of all his visits, staying at the Wynn has always been the pinnacle experience. “Because it’s the best,” he says. “The first time I came into the Wynn, I said: This is the place that God would have built if he had money.”

In the late 1980s through the mid-2000s in Las Vegas, the man with the money was, of course, Steve Wynn. “After what Steve Wynn did for Las Vegas, there should be a statue of him under the welcome to fabulous las vegas sign,” says Marc Schorr, former chief operating officer of Wynn Resorts. And while there is no statue of Wynn, who left Las Vegas in 2018, the monuments he built remain: the Towers at the Golden Nugget, the Mirage, Treasure Island, the Bellagio, and the Wynn.

As a connoisseur of Vegas, Raque knows precisely who is responsible for helping Steve Wynn make the Wynn look and feel so great. He invokes the name with reverence, as if referring to a deity.

“Roger Thomas,” he whispers.

For years, Thomas was the interior designer who took Wynn’s wildest dreams and turned them into reality. Now in his seventies, Thomas has semiretired to Italy after a long and illustrious career, but even while no longer at the Wynn in person, his presence is felt in every extravagant inch.

Roger Thomas knows Las Vegas because he is a son of Las Vegas. His father, E. Parry Thomas, was a mentor, as close as a second father, to Steve Wynn. As president of Valley Bank of Nevada, Parry Thomas helped steer the city away from mob money and into conventional financing. Roger Thomas similarly helped lead Las Vegas out of the era when, as he told The New Yorker in 2012, borrowing a line he had long heard, “every casino looked as if it had been designed by two hookers and a pit boss.”

“With the Bellagio, Steve asked me to give to him the most beautiful, most elegant hotel on planet Earth,” says Thomas, whose own elegant appearance The New Yorker described as “so relentlessly well-groomed that even his rare forays into scruffiness have an air of deliberation.” The designer rose to the challenge, creating the most luxurious and audacious resort Vegas had ever seen, a palace whose lobby ceiling is covered by two thousand hand-blown glass flowers designed by the glass artist Dale Chihuly, at a cost of $3.5 million. Then, in 2000, Wynn once again turned to Thomas and asked him to create the greatest hotel on Earth.

“If I would have known you were going to ask me to do that again,” Thomas famously told Wynn, “I wouldn’t have tried so hard the first time.”

Wynn gave him a clear mandate for the new resort that would bear his name. “If you appeal to the very most sophisticated, well-traveled, most finely educated of your guests,” the resort magnate told him, “if you satisfy them, everybody else is going to be happy.”

That mandate was delivered in the dramatic voice of a showman. “He was very commanding,” says Wynn’s longtime associate Marc Schorr. “He always stole whatever room he was in. When Steve talked everyone listened. Being a bingo operator, Steve’s father taught him public speaking. Because a person who calls bingo is a speaker. You have to have rhythm calling the numbers. B-3! and N-35! He taught Steve how to do that, and Steve used that talent in telling his stories.”

“Steve told me that if you want someone to really remember something, you pause before you say it, and you pause after saying it,” says Roger Thomas.

What Wynn told Thomas next required long pauses on both ends: “He said he wanted the Wynn to be something that no one had ever seen before, completely original.”

The result was an immense resort set on 217 verdant acres, initially with 2,716 rooms, twelve restaurants, two ballrooms, an eighteen-hole golf course, the giant Lake of Dreams, a shopping mall, an enormous spa and fitness center, five swimming pools, and, in the beginning, a Ferrari dealership.

“I’m a Ferrari collector. Steve’s an art collector, and we put his art collection in the Wynn so people could see it,” says Marc Schorr. “I said, ‘Steve, there are more people who would rather look at a red Ferrari than look at a Picasso.’ He said, ‘You may be right.’ I said, ‘There’s no Ferrari dealership in Nevada. Let’s see if we can become a dealership.’ So we got the Ferrari-Maserati dealership at the Wynn, and we had upwards of one thousand people a day.”

“I want people to be transported by the hotel,” Wynn told Vanity Fair magazine in 2005. “I’m thinking: What is it that would make people be delighted and amazed?” The resort’s brochure was even less modest. “It took Michelangelo four years to complete the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel,” visitors were informed. “Your room took five.”

The grandeur begins on the street, before guests even enter the hotel. “We had always put what Steve called a hook in the front yard,” Thomas recalls. “At the Mirage it’s a volcano. At Treasure Island it’s sinking pirate ships. At Bellagio it’s the fountain. But that, we learned, was a mistake. The best view of the fountain at Bellagio was not from Bellagio. It was from the restaurants across the street. We determined to never do that again.”

At the Wynn, the hook is as imposing as it is unmissable: a mountain rising eight stories tall, covered with towering pine trees and what seems like every species of greenery known to nature. “It’s a keep out sign on the front lawn,” Thomas explains. “It’s the mountain built in front, so you would have to come inside to see what we have.”

Past the mountain, Damon Raque and the men from Atlanta exit their taxi beneath the hotel’s porte cochere. Guiding them past two massive foo dogs—Chinese symbols of luck and wealth—Raque ushers his group through the hotel’s revolving doors, and into another world.

The lobby alone always stops the men in their tracks. Walking into the Wynn is like entering some surreal primeval forest, with its gigantic ficus trees covered in twinkling lights, from which hang enormous, multicolored flower-covered ornaments, and its extravagant marble floor inlaid with brightly colored floral motifs and glass mosaics, gleaming with natural light. Even the air here is different—fresher, more inviting somehow, instilling a fleeting moment of serenity before the senses are overwhelmed.

“I wanted, as you entered the front door, for you to have a moment of exhale,” says Thomas—the sense of relief after a long journey. “Then the next thing I wanted was for you to gasp—to inhale in awe. If you are not creating things that have never been seen before—if you are not being more dramatic, more romantic, more joyful, more mysterious, just more—then why bother? We never tried to create any fantasy except that you had arrived—that term in its most literary sense.”

The grandeur of the Wynn struck Damon Raque so profoundly on his first visit that he had to commune with the resort alone. “I wanted to be by myself,” he says. “It’s like going to a museum. It’s not fun to go with people. You have to go at your own pace.” Now, even though he has spent dozens of nights here, Raque is experiencing the resort anew, just as Thomas had envisioned. “People tend to take on the characteristics of a room,” Thomas told The New Yorker. “They feel glamorous in a glamorous space and rich in a rich space. And who doesn’t want to feel rich?”

The men from Atlanta are feeling pretty rich right now. Only a few steps inside the Wynn and they’re ready to empty their wallets, on, well, everything: the cocktail lounges, the pool services, the boutiques, the eateries. Together with its adjacent sister hotel, Encore, the resort offers more four-star award-winning restaurants than any resort in North America, its website proclaims. Before Wynn came along, Las Vegas was driven by the business concept known as loss leader. “You made money in the casino,” as Thomas puts it, “and you kind of almost gave away everything else.”

“You can experience things in Las Vegas differently than you can anywhere else in the world because of economics,” Raque says of the megaresorts that line the Strip. “Because the casinos are basically ATM machines for the resorts. You’ll walk into a restaurant, and they’ve spent twenty million dollars building out the space, right? You couldn’t spend twenty million dollars building out a restaurant anywhere else because you couldn’t make the math work on the revenue side. You’d have to charge eighty bucks for a baked potato. But when it’s part of a four-billion-dollar resort, twenty million dollars is nothing. So, the scale of what’s available—everything from the moldings and the marble and the fixtures to the restaurants, spas, and nightclubs—is just remarkable. The casinos make so much money it allows them to do things unlike anywhere else.”

Wynn recognized that every aspect of a resort—the restaurants, the shops, the rooms, the entertainment— could contribute as much to the bottom line as the gambling. If he offered the best of everything, from the biggest and most luxurious rooms to five-star meals, he’d make money before the guests even made it to the casino floor.

The Bellagio cost $1.6 billion to build, but the investment was quickly repaid. “Per guest room, the resort generated four times as much revenue as the Las Vegas average,” The New Yorker reported. In a desert town once known for its cheap buffets and lower-end strip clubs, the approach was nothing short of revolutionary. Wynn and Thomas “remade the architecture of gaming itself,” according to The New Yorker, “creating spaces that allow people to enjoy the act of losing money, thus encouraging them to lose even more.”

Every facet of the Wynn’s ambiance has been carefully calculated to seduce. The vast space is lit to resemble candlelight, “because candlelight is the most flattering light to all complexions,” says Thomas. Even the air, pumped through a massive air conditioning system, triggers a subtle sense memory. “You have to pay attention to the scent that’s in the air,” Thomas explains. “It has to smell fresh and kind of sweet. DeRuyter Butler, the architect of Steve’s resorts, always designed the air systems to exchange the air more often than anybody else did. Wynn resorts never smelled smoky. The Mirage had a floral scent. Bellagio was kind of a floral spicy scent. For the Wynn, the scent we asked for was ‘new mowed grass.’ It was designed by a scent developer. It had a tiny bit of lemongrass in it. It smelled like the best air on a spring day.”

Scent was first introduced by Wynn Resorts at the Mirage via a system called Aromasys. “We interjected a Piña Colada aroma at the Mirage,” says DeRuyter Butler. “Because when you go on vacation you like to lie on the beach with a drink, and Piña Colada is a vacation favorite. We wanted to appeal to all five senses. Most resorts appeal to three at most. But they neglect the all-important fifth sense of smell.”

The men from Atlanta are inhaling the Wynn’s intoxicating air now. Nothing as mundane as luggage is allowed to break the spell. Their suitcases and golf bags have been collected at the front door and transported by conveyor system, like the luggage of most every other guest, to the mezzanine, where the mechanics of the hotel check-in—bellhops, carts, and a baggage room—are stationed. “I always wanted guests to feel like they could be a little more dramatic,” Thomas says. “I wanted them to feel like they could make the romantic gesture, they could say the romantic line. I wanted people to feel they were in a really good movie.”

Just past the entrance garden, the Bar Parasol contains an interpretation of the famous umbrella painting by the Belgian surrealist René Magritte—eighteen giant parasols, in a swirl of colors, subtly moving up and down in what Thomas once described as a dreamlike ballet. Beyond the ballet of the parasols is the Wynn’s showpiece: the Lake of Dreams, three acres of crystal-blue water, under a fifty-three-foot-high waterfall, bubbling and shimmering in an ever-shifting display of delights. Sometimes the lake transforms itself into a rainbow. Sometimes it froths like the world’s largest glass of champagne. Sometimes surprises rise up from its depths. For many years, colored balls—one pink, one blue—magically chased each other around the lake before being joined by a little baby ball that pops up from the depths, a comic ending to a flirtatious pas de deux. Once, when country music superstar Garth Brooks was celebrating his birthday at the SW Steakhouse overlooking the lake, a twenty-five-foot animatronic frog wearing a cowboy hat arose from the water and serenaded him with a twangy “Happy Birthday.” The frog, created for the Wynn by a Disney alumnus, was said to have been designed to help persuade Brooks to emerge from his retirement and perform once more on the Wynn’s main stage. The frog—along with a big paycheck, transportation by private jet, and most importantly, “his personal ‘testing’ of the Encore theater for its acoustics and amenities,” says DeRuyter Butler, the resort’s architect—sealed the deal.

To ensure that every guest has a stunning view of the lake, an expensive solution was devised. Instead of installing conventional, straight-line escalators, which had blocked the view of the fountain at the Bellagio, they purchased two of what were then the few existing curved Mitsubishi escalators in the United States, which now cost around six million dollars each.

“It’s the wow! moment,” says Damon Raque, who revels in the sight of the Wynn’s lake on each visit. “Because the escalators are curved, you look out and see the entire Lake of Dreams. It always makes me want to work harder at home to be able to come here, while also forcing me to slow down and appreciate the moment. It’s inspiring. It sets the tone.”

Now, even before going to their rooms, the men from Atlanta are ready to hit the casino, where they can hear the jangle of slot machines. There, Thomas had yet another mind-bending innovation. “We wanted to make the gamblers feel they are playing at their blackjack table, their roulette table, their craps table,” he says. “Steve always asked me to think of intimacy. But making a large place feel intimate and personal is a great challenge.”

On the surface, the solution Thomas came up with seemed simple: placing chandeliers over every table in the Wynn’s cavernous casinos. The problem was, the chandeliers blocked “the eye in the sky,” the high-tech array of cameras the casino’s security team monitors to catch cheaters and card counters. “Steve allowed me to spend a fair amount of time and money developing a chandelier equipped with integral cameras, and we were able to prove that they not only provided the view prescribed by the Nevada Gaming Control Board, they improved it,” Thomas recalls. The Wynn patented the devices, but thus far, no other casino has tried to copy the idea. “No one else understood that having a chandelier over a gambling table makes you instantly relate to your dining table or your kitchen table in your home.”

“There will never be another Steve Wynn, who would take the time and spend the money for the right resort,” says Marc Schorr. “Today the Wynn stands above all other resorts and is still the number one resort in Las Vegas in occupancy and revenue.”

For Raque, the Wynn is a cathedral of inspiration. Even after all his years coming to Vegas, all the wild days and crazy nights and high-priced thrills, he’s still looking for a way to do the seemingly undoable, still in search of something new and radically different than anything he has done before. The Wynn makes him want to top himself, just as the resort topped what Wynn, Thomas, and their associates had achieved with the Bellagio.

“It makes me determined to commit to excellence in my own life,” Raque says. “To create a Vegas experience as beautiful and impactful and memorable as the hotel.”

By the time he enters his room, high in the Wynn Tower Suites, overlooking the golf course and the mountains and desert beyond, his audacious new idea to top all he has done in Vegas before has arrived.

♣ ♣ ♣

Chapter 4

THE VIP HOST

THE VIP WING OF A MAJOR LAS VEGAS RESORT

THE GAMBLER IS prepared to spend a fortune.

He’s a mystery man from overseas, a roulette player. Eddie, a VIP host, gets a call from the man’s associate, stating that the gambler plans to “post”—meaning place money on deposit in the casino—around one million dollars in checks.

Eddie is paid a sizable salary to field calls like this. As a VIP host, his job is not only to fulfill the needs of every guest, no matter how last-minute or outlandish, but also to handle minor setbacks and full-blown crises with an equal measure of courtesy and calm—especially when a gambler is prepared to post a million in his resort.

As he speaks to the associate, Eddie does a quick online search of the gambler’s name. The guy looks legit: he’s an international businessman, so his checks should be good. “We always have to verify the checks,” Eddie explains, “to be sure there’s no holds or stops on them.”

But there’s one snag: the gambler needs transportation from Los Angeles. Can the resort send its jet to pick him up?

Now Eddie is the one who has to gamble. The flight is less than an hour from Los Angeles to Las Vegas. But sending the resort’s jet won’t be cheap. It’s “a beautiful plane,” Eddie says, and the round-trip flight will cost the resort around twenty thousand dollars.

It’s a white-knuckle moment for the VIP host. Is the gambler good for the money? Is he a whale? Or a wannabe? Time is of the essence. The associate has already sent the checks to the casino, and the credit department has begun the process of trying to confirm them. The gambler is waiting for an answer.

The VIP host checks with his boss, but it’s really just a formality. Eddie is a very experienced host. He’s come through with major players in the past, and his boss trusts him implicitly. It’s pretty much his call.

Eddie sends the plane and awaits the verdict.

♣

Standing at his post in the luxurious VIP area of the resort and casino that is his second home, Eddie could be part of the resort’s opulent design. From every aspect of his ultra-hospitable demeanor to his friendly manners and copious charm, he serves as a best friend to well over a hundred regular clients. This morning began like every other: on the phone.

“I woke up and there were fifteen texts from people and a few phone calls,” he says. “It’s people just needing things. Because we live in a society where everyone is so last-minute. And I get it. They’re on vacation. They have needs and wants, whether it be dinner reservations or a limo ride. There are a lot of last-minute details that need to be ironed out before their trips. And unfortunately, everyone waits until twenty-four hours before they come.”

VIP hosts form a veritable army in Las Vegas, hundreds of men and women whose mission is to attend to the high rollers who flock to the most exclusive wings of the city’s most exclusive resorts. Once these clients arrive, it’s the job of the VIP hosts to keep them there, dining and drinking and gambling in the all-encompassing worlds that begin and end at the resort’s VIP entrance. The hosts don’t just arrange reservations at exclusive nightclubs or tickets to a Lady Gaga concert—they often accompany their clients when they go out at night, partying with the high rollers before ushering them safely back to their VIP accommodations.

Eddie has been attending to guests since he arrived in Las Vegas years ago. He had traveled a fair amount and wasn’t looking to settle permanently, but a friend who was working in Vegas uttered the magic words: Why don’t you apply for a job here? And, just like that, Eddie could envision his future.

He quickly realized that the real money and gratification wasn’t in hotel management but in managing VIPs. His tremendous work ethic and easy smile quickly got him elevated to the VIP check-in desk at his first major resort. “That’s where I met this amazing cast of characters,” he says. “We got everybody—Tom Cruise, Nicole Kidman, Michael Jackson. Big, big, big celebrities.”

And not just fame. There was money, and lots of it. “People would come with big bags full of cash,” he says. “It was like something out of the movie Casino,” the 1995 Martin Scorsese movie starring Robert De Niro and based on the life of Frank “Lefty” Rosenthal, who managed Vegas casinos for the Chicago mob.

There was also royalty. “It was the first time I saw a royal title on a credit card,” Eddie says, recalling a certain aristocrat rolling up with her retinue in grand style.

Along the way, Eddie learned the fine art of anticipation, knowing what guests need “before they arrive at the hotel, or even think of it themselves.” Whatever they desire—from sports or concert tickets to stocking their rooms with beverages, flowers, and other amenities—the veteran VIP host is there. “If they’re celebrating a special occasion like a birthday, I arrange for theme cakes, and special tables at restaurants, along with shopping excursions at the stores where I know the salespeople,” says Eddie. And there are the cars, a vast array, dispatched with chauffeur to ferry the chosen around town. He’ll do anything and everything—except provide companionship for the evening. “I’m often asked, but politely decline to assist in that area,” he says. “Because it’s illegal.” There are legalized brothels in rural Nevada, but not in Las Vegas.

As Eddie reminisces, his phone rings. It’s always ringing. It’s only nine in the morning, but he’s already fielded a dozen calls. His phone is his command center, buzzing and pinging and lighting up around the clock, 365 days a year. He used to sleep with the thing, but then he couldn’t sleep. Because his clients never do. “They need things,” he says. “Always needing things.”

And Eddie has learned never to say no to anything legal—no matter how bizarre or eccentric the request. “This is their recreation, and I’m the person who facilitates all of it for them. I’m important in their lives, because I’m their fun. This is their Disneyland.Disneyland for adults.” On the phone is a cherished client—meaning, above all, a big spender. “I would say, anywhere from fifty to a hundred a day. Thousand. Comes to gamble. Mostly slots.” But as Eddie listens, his seemingly perpetual smile vanishes. “Oh, no!” he says. “You’re kidding? Oh, no! I’m so sorry to hear that.”

His client is entangled in some sort of crisis.

“Oh, I’m sorry. Oh, boy! Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. Right. Sure, I’m the same way. I’m so sorry!”

He hangs up, wishing he could rush over and console his client. “I genuinely like people,” he says. “And when they’re in trouble I want to help them.

“You become friends with your clients, and that’s the beautiful part of my job,” Eddie says. “Because I find them fascinating, these people. They run big businesses, and I learn a lot from them. But they’re also just nice people.”

♣

The tradition of providing guests with VIP hosts began like so many other Vegas innovations—back in the swinging, ring-a-ding-ding era of the 1950s and ’60s Sands Hotel. Gamblers arriving on junkets from New York, Chicago, and Miami needed someone to get them reservations for dinners and shows. And the casino needed someone to set up the credit lines for the gamblers.

“The casino host was the top credit manager, taking care of VIP players,” explains Ed Walters, who served as a pit boss at the Sands during the 1960s. “But we didn’t want to say ‘credit manager.’ We wanted a word to say, ‘We’re here to help you with whatever you need.’ The Sands was very service oriented. The floorman was watching the games. The pit boss was watching the pit, which was my job. And then you had someone who walked around everywhere—the restaurant, the casino. He was there to help our good players with whatever they needed. And that person came to be called the host.”

The first to assume the host role at the Sands? “My father, Marty Goldberg,” writes Anne Hodgdon, adding that Marty’s uncle, Texas oilman Jake Freedman, was the president and principal owner of the legendary resort until his death in 1958. Freedman introduced the “eye in the sky” surveillance cameras that all casinos now use, and he imported gaming executives and others, including Marty Goldberg, from across America to serve his clientele. “Perhaps you could say my dad coined the ‘host’ identity in Las Vegas,” says Hodgdon.

Goldberg first came to Las Vegas from Philadelphia to oversee the liquor operations at the Sands’s Copa Lounge, a role that quickly expanded into something new. Red Norvo, a jazz musician who played the Copa Lounge, wrote a song called “Marty’s Walk” to “pay tribute to the way my father walked all night, greeting people and making them feel important,” says Hodgdon.

“His key role,” she continues, “was to know ‘who was who,’ and to ensure they were recognized and treated like royalty while guests at the hotel.”

The VIP hosts not only accommodate guests once they’ve arrived; they also bring VIPs into the resort. When Steve Wynn bought the Desert Inn Hotel and Casino, which would become the site of the Wynn, he put “his whole bankroll at risk,” says the longtime Wynn associate Marc Schorr. “We didn’t know it was going to be a success. We knew we had to make a destination hotel; we had to make it the place to be. Bellagio was surrounded by resorts with thousands of rooms. But the site of the Wynn had none of that; it had a closed Frontier across the street, a closed Stardust nearby. You had to build your customer base one customer at a time.”

Having sold Mirage Resorts to MGM, Wynn was left without a customer base. “The new owners kept our customer base,” says Schorr. “To build a new customer base, we fished where the fish were.”

And those doing the fishing were the VIP hosts. “We’d go to the racetrack, where the people at the clubhouse were the customers we wanted,” Schorr continues. “We’d have a Wynn table in the clubhouse. If one host couldn’t hook the guy, we’d send another host to get him. Eventually we got them all. In the end, you’ve got to build a better mousetrap where the customer wants to be.”

♣

Today, gaining access to VIP hosts like Eddie and the VIP suites and towers that have been built in most of the major Las Vegas resorts—complete with their own private entrances and elaborately designed lobbies—is based on a gambler’s “spend,” a system of carefully calibrated tiers. “We rate customers based on their playing,” says Eddie. “They start out at the casino rate. That’s somebody you just want to encourage to come. You give them a little bit of a discount, say 10 to 15 percent off the room rate.” The same discount applies to “guests of”—friends of established gamblers. “I put in the rooms at the casino rate, to give them a little discount,” he continues. “But they still check in at the regular front desk.”

To get to the VIP hosts and the VIP suites, guests must be prepared to spend serious money at the tables. “My guests start at five thousand dollars in play,” Eddie says, meaning the amount a guest commits to playing during their stay. “That probably gets them a room comp.” The next tier are the RFB players—meaning room, food, and beverages are all on the house. “RFB begins when they have a budget of ten thousand dollars, and they play to it,” Eddie says. “You can’t just have it sitting there. It has to be in action, whether at the tables or the slot machines.”

The casino attempts to determine the precise level of play. Supervisors track the players’ wagers at the tables, and loyalty cards, which players insert into slot machines, automatically show their level of play. This enables the players to be rated by the casino, although some players prefer to play in anonymity. However, being rated and being issued a loyalty card enables the gambler to earn complimentaries, or “comps.” Once issued, the gambler takes the player’s card to either the table or the slot machine, and their play is tracked. Hopefully, just a small percentage in cash, “because we don’t want people taking the cash out of the casino and buying things,” Eddie notes. “We want them to use it for gaming purposes only.”

Most VIP hosts have to hustle to get their clientele. Not Eddie. “I do very little marketing,” he says. “Since I became a host, most of my gamblers are established clients or come to me by referrals from other players. So it’s just about fielding phone calls.” They come from all over: from Venice to Vancouver, from Paris to Prague, from Minneapolis to Madagascar. “But I would say the majority of my people are within driving distance. Seventy-five percent are from California, Arizona, Colorado, and Texas.”

The biggest gamblers have always come from the most lucrative industries, be it oil and gas or mining and manufacturing. In his younger days, Eddie would party with his clients. “But now that I’m older, I don’t. And believe it or not, I’m not a gambler. I don’t gamble one penny.” Nowadays, he sticks to dinners, opulent affairs with his favorite whales. “I had a very high-high-high-high-end client,” he says. “He had a very big personality. He’d come in with four hundred thousand dollars.” They’d dine together at luxe French restaurants, where they’d drink Petrus, the most expensive Bordeaux, with every course, then rare Cognac with dessert—the bill sometimes running over ten thousand dollars.

His phone rings. “Hi, buddy. Did you miss your flight? Oh, okay.” The client has left something valuable behind in his room, as they often do. “I’ll run up there and get it. Do you want me to have it shipped to you? Or I can hold on to it if you’re coming back soon. Yeah, I’ll hold on to it. Oh, you’re welcome. My pleasure! All right, have a safe trip home.”

Eddie remembers how he once landed a client. “He was going to a blackjack tournament at another casino, but they sent an older plane to pick him up,” he recalls. The guest was upset. “So he called me up.”

Send your best private jet, the guest said, “and I’ll be a customer for life.”

It was early morning, and Eddie had to move fast. Was the jet available? Would it get to his guest in time to fly back to Vegas for the tournament? “I really had to scramble,” Eddie said. “I was under the gun—there was a lot of pressure to do it.”

The VIP host pulled it off. The guest opened a major line of credit. And he’s been loyal ever since.

♣

The plane is in the air, en route from Los Angeles. The gambler is on board, headed to Vegas. Throughout the flight, Eddie has been working with the credit department to confirm the checks. If there are any problems, then the VIP host is in trouble, along with the gambler.

Just before the plane touches down, word comes in that the gambler is good for the money. The checks will clear. Eddie rolls out the red carpet.

As soon as the gambler lands, the pampering begins: the limo from the private airport, the seamless arrival through the VIP entrance to the suites in the sky. The whale is dressed casually. He knows no one here, but his connection to Eddie is enough.

In the end, the guest doesn’t turn out to be much work for the VIP host. He spends almost all his time in the casino, asking only for dinner reservations. He winds up playing “the full line,” meaning he gambles his entire line of credit—all of which he loses.

But he loses it happily. “It was very quick, in and out,” says Eddie. “He didn’t even spend the night. We ended up flying him back that same day.”

As the whale leaves for the airport, his associate turns to Eddie and says the words every VIP host longs to hear—especially when his gambler is leaving a loser.

“He had a great time,” he says of the gambler. “We’ll be back.”